An American White Supremacist’s New Home in Serbia

Robert Rundo’s latest video opens with the 30-year-old native of Queens, New York, showing off Serbian nationalist graffiti adorned with a Celtic cross, a well-known white supremacist symbol.

“So we’re out here in Belgrade, you know, cleaning up the neighborhood,” says Rundo, pointing to what he calls some “beautiful artwork from the locals” behind him.

These locals are apparent far-right comrades of Rundo’s, repainting white supremacist graffiti that had been defaced days before by local anti-fascist activists.

Rundo is the co-founder of the Rise Above Movement (RAM), an American white supremacist gang that saw three of its members imprisoned for violence at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017; two are still incarcerated. A separate federal case against Rundo himself for similar violence in California was dismissed in June 2019. Since then, he has been a free man, although federal attorneys have sought to challenge this outcome and an initial appeal hearing took place this week.

A screenshot from a November 8, 2020 video from Robert Rundo’s Telegram channel, showing him in front of far-right graffiti in Belgrade, Serbia

The video was posted on Rundo’s Telegram channel on November 8, 2020. What is striking about it is not Rundo’s promotion of openly violent imagery, or that he is wearing a shirt from his own far-right fashion brand. It is the location: the Serbian capital Belgrade.

It has been publicly documented and reported that Rundo has spent much of 2020 across eastern Europe, spending time in Ukraine, Hungary, Bulgaria and particularly Serbia.

But it is Belgrade where Rundo appears to be trying to build a base for himself. Rundo has even gone as far as to incorporate a company in Serbia, which would allow him to apply for temporary residency in the country. With the possibility that Rundo may eventually face a new trial in the United States as a result of this week’s aforementioned appeal hearing, however, it seems fair to suggest his activities in Serbia deserve greater scrutiny.

Rundo and the Rise Above Movement

The Rise Above Movement was co-founded by Rundo and fellow American Ben Daley in 2017 in southern California. Rundo had a history in gang life, as outlined in a 2017 ProPublica investigation, and served 20 months in prison for a 2009 assault where he stabbed a member of a rival gang five times. After his release, Rundo moved from New York to southern California.

The group of a few dozen young men in RAM, rather than mix up in the online battles being fought by the ‘alt-right’ at the time, preferred to focus their energies on mixed martial arts (MMA) and physical training — gearing up for the purpose of “physically attacking [their] ideological foes.” As a 2018 PBS Frontline documentary noted, RAM’s social media posts at the time featured white supremacist and openly anti-Semitic imagery, and even showed them training with the Hammerskins, a neo-Nazi American skinhead gang.

Clad in skull masks and hands wrapped like MMA fighters, members of RAM violently attacked anti-Trump protesters and others in California as well as at at the Unite the Right in Charlottesville in August 2017.

In-depth investigations in 2017 by ProPublica and a subsequent PBS Frontline documentary in 2018 brought public attention to Rundo and RAM’s assaults at these rallies. Journalist Ali Winston wrote in an October 2020 profile of Rundo (Winston contributed to both ProPublica and PBS Frontline’s investigations) that Rundo’s personal life was upended by the publicity — he lost his job and his then-fiancee left him.

These journalistic investigations also drew law enforcement attention to RAM and Rundo. Four RAM members who took part in violence at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville were arrested in 2018. In 2019, the four men pleaded guilty to federal rioting charges; two of them, including RAM co-founder Ben Daley, are still incarcerated. In their pleas, they admitted their actions were not in self-defence.

Separately, Rundo and two of his colleagues were charged in 2018 under US federal anti-riot legislation for their apparent violent actions against counter-protesters at several California pro-Trump rallies in 2017. Rundo sought to make himself scarce; he tried to flee to Ukraine, and then fled to El Salvador, where he was soon arrested and brought back to the United States.

However, a California judge dismissed Rundo and his comrades’ case in June 2019, stating that the federal act under which the trio were charged was too broad. It is this ruling that federal attorneys have sought to challenge, with oral arguments for the appeal taking place in a federal appeals court in California earlier this week. A ruling — in short, a decision on whether or not Rundo will face a new trial — is not expected for weeks or months.

“The Power of the Image is Extremely Important”

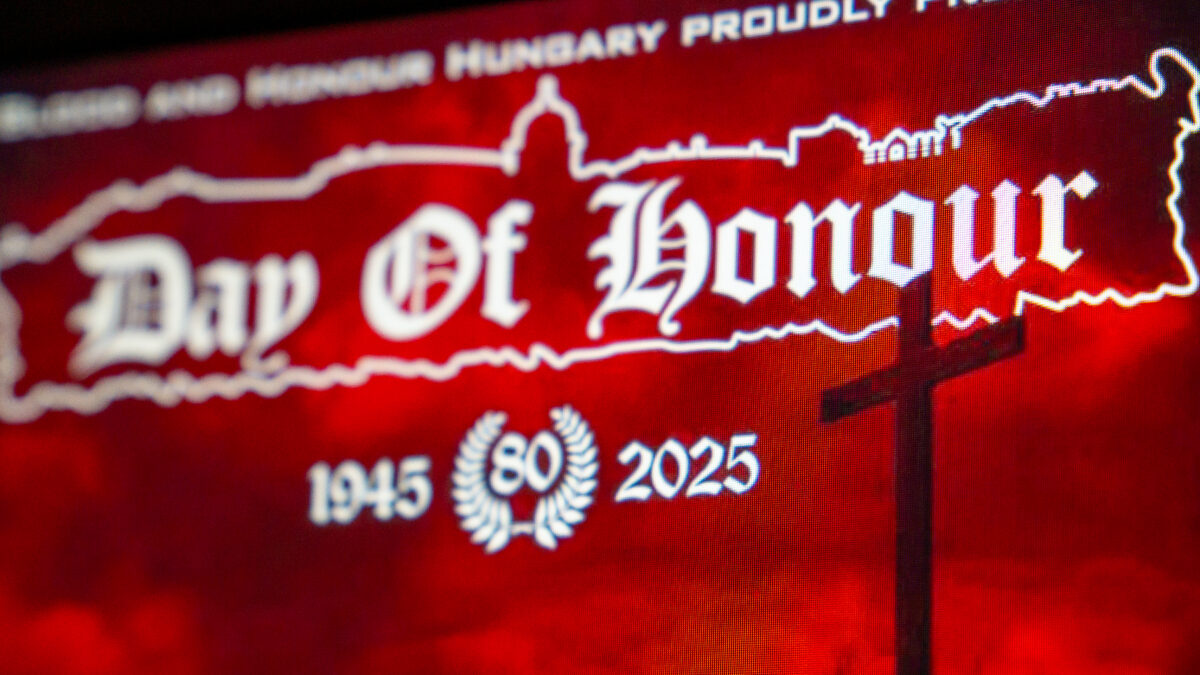

Rundo has spent much of 2020 in eastern Europe. He attended a neo-Nazi commemoration in Budapest, Hungary in February 2020. Two weeks later he was in Sofia, Bulgaria for an annual neo-Nazi march that, for the first time in years, was banned by local authorities, with only a small commemoration to a Nazi-collaborating general taking place (the author of this article covered both events). In an interview with a neo-Nazi podcast in September 2020 — one in which Rundo spouts the n-word, uses anti-Semitic language and references Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf — Rundo claimed he left the United States because of “non-stop harassment” from American law enforcement.

More recently, Rundo has shifted his focus to media and propaganda. He has created a website and a planned documentary series meant “as another way of creating a counter-culture to the left by covering everything from demonstrations, concerts and creating our own entertainment within the nationalist lifestyle way (sic).”

On his YouTube channel, Rundo appears in videos offering advice on everything from organizational tactics and physical training to graffiti and travel tips. The first of the documentary series is a nine-minute video of Rundo and a RAM colleague’s trip to Bulgaria take part in the banned neo-Nazi Lukov March.

A separate website features occasional articles by Rundo and others, including English-language translations of Russian-language pieces by Ukraine-based neo-Nazi group Wotanjugend.

Rundo has also started up a far-right fashion brand, whose clothes the website proclaims are exclusively made in eastern Europe and that “not a single hand touches the production that is not of like mind.”

The focus of these efforts appears clear from Rundo’s online output and his own words: image.

“The only images the left can use is shit that we already put out, so you know it’s going to look good and it’s going to attract people that way,” Rundo said in the September 2020 neo-Nazi podcast interview. “The power of the image is extremely important. I think we really need to pay attention to and control our image.”

Still, Rundo has yet to translate that image into any significant far-right media fame. His YouTube channel has just over 1,000 subscribers, and no video has more than 2,800 views as of mid-November 2020.

From SoCal to Serbia

Rundo didn’t just pop up in Serbia in November 2020. A March 2020 video featuring Rundo giving his “thoughts over tea” was quickly identified by Bellingcat as being from a cafe on Belgrade’s Knez Mihailova, the Serbian capital’s main pedestrian and shopping street.

A photo of the location of Robert Rundo’s March 2020 video in Belgrade, Serbia (Credit: Michael Colborne)

In July 2020 Rundo appeared in a YouTube video at an event hosted by a Serbian nationalist organization called Fondacija Junak (“Hero Foundation”). The video, posted on Rundo’s YouTube channel on July 7, 2020, also shows an unfurled “Free RAM” banner, referring to Rundo’s RAM colleagues who remain incarcerated.

Rundo even made an appearance in local Serbian TV coverage of Fondacija Junak’s event, giving his name as “Roman.”

In August Rundo also appeared in, of all places, a Serbian nationalist rap video.

Putting the Pieces Together

More recently, however, Rundo has generally been reticent to openly reveal his location, his most recent video notwithstanding. In the above-mentioned September 2020 neo-Nazi podcast, Rundo even stated he had left Serbia.

But there are enough hints from Rundo’s own social media and those of his friends and colleagues that made it clear, even well before Rundo’s most recent video, that he was still in the country or had left and returned. Moreover, these hints are an instructive tool for those wishing to keep an eye on the actions of far-right figures: even when they and their friends are trying not to give away their exact location, they often reveal enough clues along the way to make it clear where they are.

In a YouTube video posted on October 1, Rundo appears on a lakeside with mountains, hills and rock formations in the background.

Thanks to the unique nature of the rock formations, Bellingcat was able to geolocate where the video was filmed: Lake Perucac, Serbia, along the country’s border with Bosnia and Herzegovina and a popular vacation spot.

On October 28, Rundo posted a photo of a far-right sticker at a bus stop to his Telegram channel. The open-source research on this photo, however, required a little bit of luck. The author of this article recognized some of the physical features in the picture, particularly the concrete planters visible in the median of the street, and went and confirmed the location in person October 29. The same sticker Rundo had photographed the day before was visible.

A photo, taken October 29, 2020 of a sticker posted on Robert Rundo’s Telegram channel the day before (Michael Colborne)

On October 30, Luka Karadzuleski — a 19-year-old Belgrade videographer, photographer and web designer — posted a public Instagram story (a video that deletes after 24 hours) showing Robert Rundo being interviewed by an unknown TV crew. Karadzuleski lists “W2R,” the official short name of Rundo’s company, as a client on his personal website, and he is listed as the creator of the Fondacija Junak video from July 2020.

“[Robert] Rundo reached out to me looking to hire someone who can do good enough videos [and] photos,” Karadzuleski told Bellingcat by email. He added that he was “not that much into political things” and was hired by Rundo to “record a few behind the scenes videos.”

A screenshot of Luka Karadzuleski’s now-deleted Instagram story from October 30, showing Robert Rundo being interviewed by an unknown TV crew.

In the background of the video, near the end, the words “Smurfit Kappa” can be seen in the distance on a building. Smurfit Kappa is a European paper manufacturer whose Belgrade factory is on the banks of the Danube.

A screenshot of Luka Karadzuleski’s now-deleted Instagram story from October 30, showing a name on a building.

Thanks to this, Bellingcat was not only able to geolocate the place of the video to a nearby site along the Danube, but was able to visit the site in person, confirming not only that this was indeed the site of the video, but also located the presence of “Free RAM” graffiti that had been featured on RAM social media for several months.

RAM graffiti on the banks of the Danube at Ada Huja in Karaburma, Belgrade, Serbia in November 2020 (Credit: Michael Colborne)

A Ticket to Residency in Serbia?

But Rundo has done more than just make videos and show off graffiti in Serbia. Public records indicate that Rundo incorporated a company in Serbia — “Will2Rise,” the name of his far-right fashion brand. And it could just be the ticket Rundo needs to get residency in Serbia.

Publicly-available records on the Serbian business register’s website show that Rundo incorporated a limited liability company (D.O.O.;”društvo sa ograničenom odgovornošću” in Serbian) on July 23, 2020 called “Will2Rise doo Beograd-Palilula”. Palilula is a municipality in the city of Belgrade. Incidentally, Rundo incorporated a company with the same name in Florida in October 2020.

Robert Paul Rundo — Rundo’s full name, as is clear from American court records — is listed as the sole legal representative and sole owner of the company. The starting capital invested in the company was 100 Serbian dinars, about €0.85 or 1 American dollar.

Serbian public records also include personally identifiable information about Rundo, including his date of birth, American passport number, two addresses in Belgrade and a Serbian mobile phone number, though that number appears to be invalid or no longer active.

“[W]ow your (sic) a regular sherlock homes (sic),” Rundo responded to Bellingcat’s request for comment by email, “finding public info i put out.”

Bellingcat visited the address associated with Rundo’s company in early November 2020. The location is in Karaburma, the same area of Belgrade as the “Free RAM” graffiti and the location of the October 30 Instagram story. At this address Bellingcat observed a man wearing a “Serbon” brand shirt — a Serbian far-right fashion brand that features Rundo as a model for its clothes and also sells and distributes Rundo’s clothing brand — loading boxes of goods into a car.

Serbon’s clothes feature white supremacist imagery, including the kolovrat, a symbol commonly used by neo-Nazis in Slavic countries, as well as masks bearing a Celtic cross, another common white supremacist symbol. Stickers for Serbon were also visible on poles and walls around the immediate vicinity of the address.

When reached for comment, a Serbon representative told Bellingcat that they “personally haven’t met him” and “probably [Rundo] didn’t want to meet to get too well-known.” They also denied knowing that Rundo had ever registered a company in Serbia, and claimed their only relationship with Rundo was selling clothes from his far-right fashion brand.

But Rundo’s incorporation of a company in Serbia may not simply be for business purposes. In Serbia, a foreigner who incorporates a company can apply for temporary residency for up to a year at a time, and can renew this residency with a new application every year. In short, this would allow Rundo to build a semi-permanent legal base in a European country without having to worry about visa-free regulations that limit American citizens to spending no more than 90 days within a 180-day period in Serbia.

What Now?

Rundo would not answer questions about whether he planned to or already had applied for temporary residency in Serbia, or whether he had returned to the US for his appeal hearing on November 17, though the hearing was via Zoom with only lawyers present and he was not required to appear.

If the federal government’s appeal is dismissed, like the original case, Rundo remains a free man. However, if the federal government’s appeal is granted, Rundo would eventually face a new trial. Serbia has an extradition treaty with the United States, but no one has yet been extradited to the US from Serbia as a result of the treaty, which only came into force in April 2019.

With his past history as someone who has tried to evade and escape justice, what Rundo does in Serbia might soon take on a new urgency. Moreover, it may provide a blueprint for other far-right extremists seeking to avoid scrutiny at home.

With contributions from Oleksiy Kuzmenko