Tracking Down Corruption in the Defence Sector in MENA

Transparency International’s Government Defence Index is a unique resource that collects evidence and insights on malpractice in the defence and security sector, worldwide. The most recent version was released today. As the majority of the research for this project involved gathering openly accessible information online (with a very limited part of the evidence coming from closed sources), the resource serves as a handy example of the depth and detail of the research on fundamental compliance issues in the defence and security sector that can be exposed with open source intelligence (OSINT).

Today, corruption watchdog Transparency International is rolling out the first chapter of its Government Defence Index (GI). This index is a unique and comprehensive resource for all things transparency and accountability as they relate to the defence and security sector. The detailed results and methodology assessment are available on the index’s dedicated website.

The rationale behind the MENA-focused GI is the following:

Defence corruption erodes the ability of the state to fulfil its primary obligation – to protect its citizens. It means countries do not have the right military capabilities, do not deploy strong strategies and cannot rely on the competence and loyalty of their personnel. This report aims to identify how corruption risk and a lack of accountability is contributing to the fragility of governments, and what this means for the prospects for security and stability across the Middle East and North Africa.

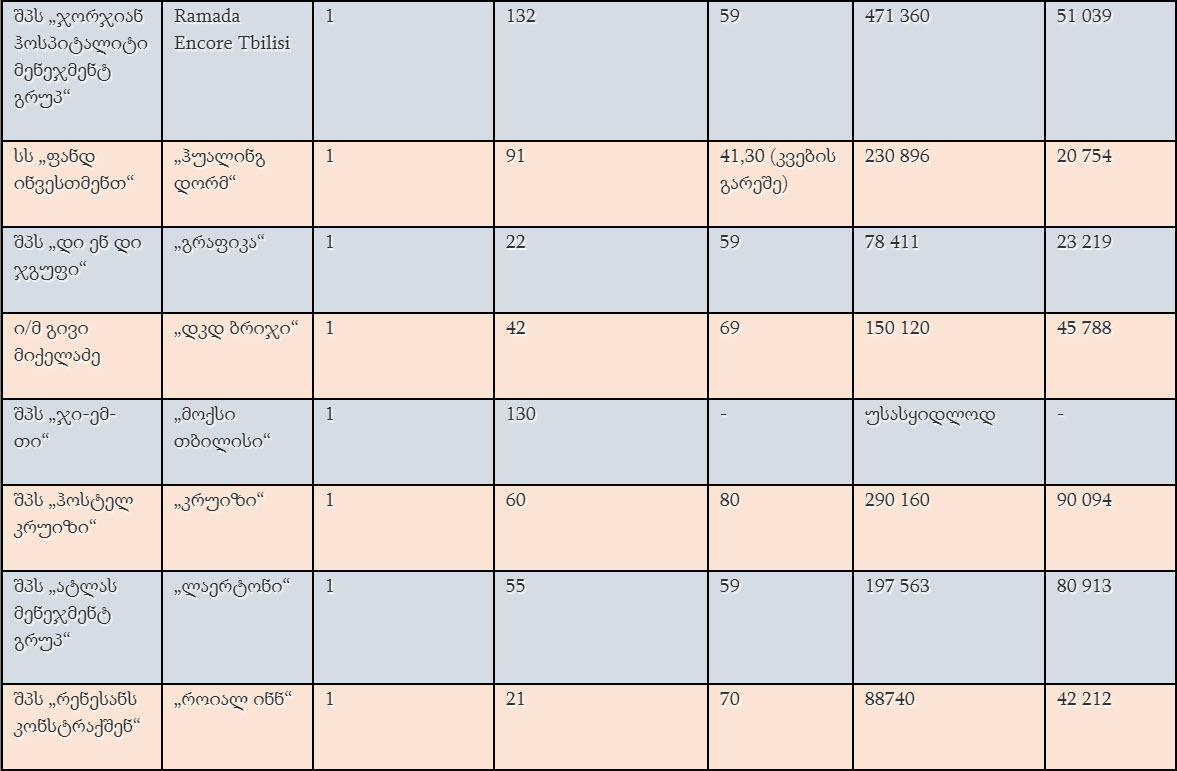

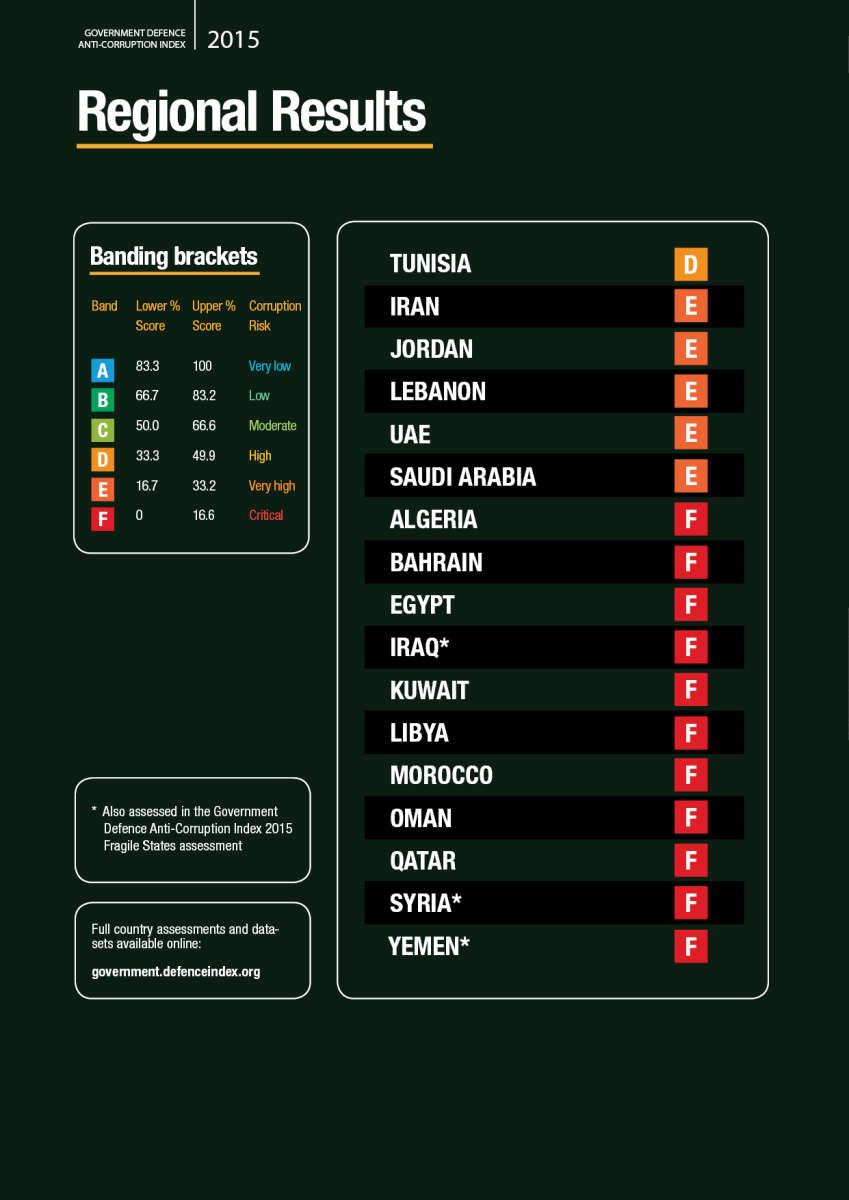

The most recent edition of the GI thus finds that the overwhelming majority of the MENA countries fall in the highest, most severe risk category for corruption in the defence and security sector (marked ‘F’ on the map below). The remaining countries are either at moderate (Tunisia) or high risk (Lebanon, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia).

An overview of transparency rankings for the countries in the MENA region. Image used with permission, courtesy: TI Defence Index. Click to view full size.

For each country, a consistent OSINT approach had to be employed, given that potential interviewees did not agree to answer questions for fear of repression. Indeed, many of the MENA countries punish such inquiries with prison time. This piece aims to highlight outcomes rather than provide (methodology) detail for each and every output mentioned below. Indeed, this would constitute a useless duplication of information with the actual country reports available on the GI website. At last, exploring detailed reports for each country is highly recommended as it provides insights about the difficulty to demonstrate and bring proofs about issues that have little to no solid factual existence (e.g., spending and offsets).

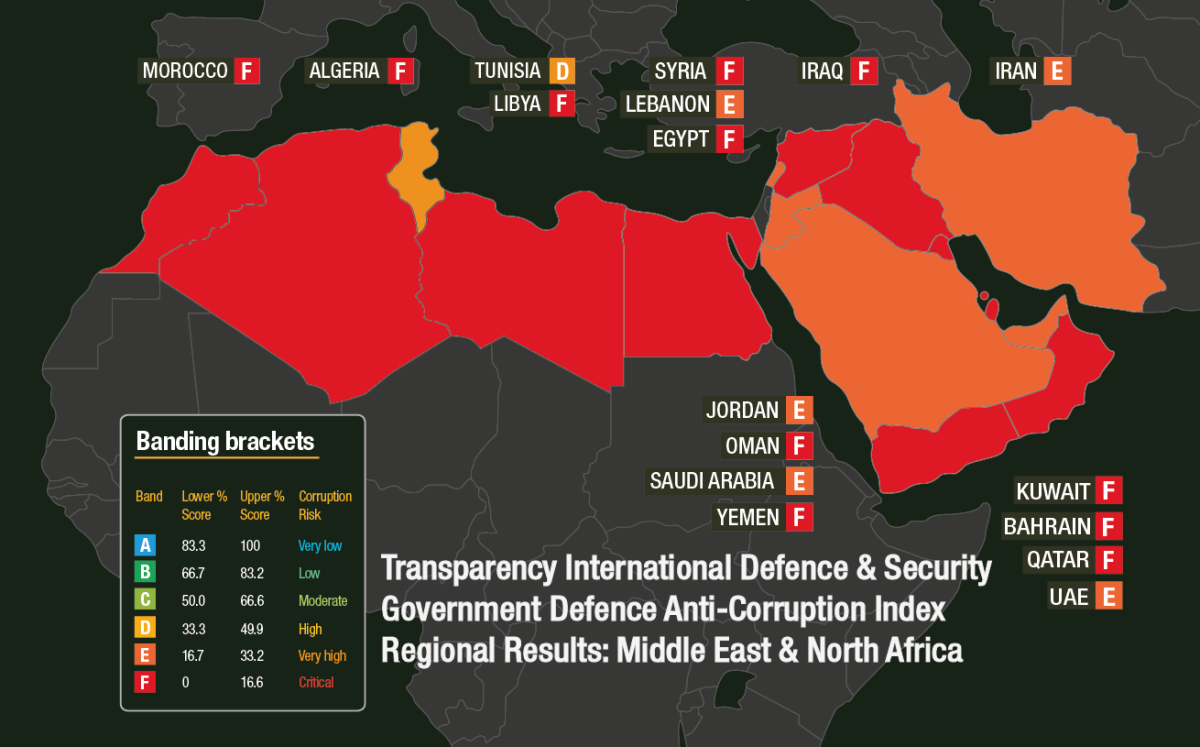

The assessment methodology is straightforward. The levels of corruption risk in national defence establishments are scored in five risk areas: Political Risk, Financial Risk, Personnel Risk, Operations Risk, and Procurement Risk. To produce the scores, a standardised assessment, consisting of 77 questions, was used; for each question, the government was scored from 0-4, with ‘0’ indicating weak or no activity to address corruption risk and ‘4’ meaning strong, institutionalised activity to address such risks. The rankings’ overall percentage determined which category the government was placed in:

Meaning of transparency rankings and overview of MENA countries. Image used with permission, courtesy: TI Defence Index. Click to view full size.

To support scoring for each of the 77 questions, substantial proof and multiple sources needed to be provided. But, as mentioned above, sources rarely agreed to respond and often provided only succinct, general information. Official government websites and offline publications, when they exist, do not provide with accurate figures either. Thus, for instance, Algeria‘s entire defence budget is classified, and no details on defence spending are available. External sources, such as defence-focused foreign publications, estimate that the Algerian army’s budget was 20 billion USD in 2014, the highest in Africa. No defence-specific committee in Algeria’s parliament exists either, thus there is no parliamentary oversight of defence spending. This situation is common to all countries in the region, Tunisia and Jordan being the only exceptions by publishing some details of their defence spending.

The openly available evidence collected in the process of research indicates, however, that secrecy of defence spending entails a lack of scrutiny for billions of dollars:

- The MENA countries studied in the GI spent more than 135 bln USD on military expenditures in 2014. This amount is equivalent to 7.6 percent of global military spending.

- As a percentage of GDP (5.1 percent), MENA countries’ defence spending is the highest in the world. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, for example, reports that defence and national security spending comprises 30 percent of government budgetary allocations.

- Since 2010, Saudi Arabia and the UAE were among the five largest importers of major weapons. Thus, according to the most recent numbers from SIPRI, Saudi Arabia has undertaken the world’s most massive spending increase of 17 percent between 2010 and 2015.

Military expenditure changes in the MENA region for 2013-2014. Source: SIPRI 2015. Image by the author.

Overall, the region, where secrecy remains the norm, currently accounts for about over a quarter of the world’s defence spending.

Defence and security procurement is another facet of the story. Military capability is severely undermined by the lack of doctrine and the absence of national defence strategies. As the GI MENA report highlights:

Acquisition planning—the process through which the state identifies what arms it will buy—is unclear or non-existent in every state studied. As a result, individual decisions consistently appear to override technical needs.

Such poor and non-strategic procurement has bizarre outcomes:

- Qatar has, for example, recently vowed to purchase 118 Leopard tanks and 16 tank howitzers from Germany in preparation for the 2022 World Cup, but no explanation or details exist as to how this gear is supposed to improve security during the soccer event.

- In Saudi Arabia, defence purchases are often opportunistic by nature and serve to strengthen alliances. This is, again, poor acquisition planning, and has resulted in obtaining different platforms that serve the same purpose. Thus, publicly available evidence allows to tell that the Kingdom now has large numbers of duplicative weapons systems, e.g., Typhoon and F-15 fighter jets, as well as comparable armoured personnel vehicles bought from Canada, Serbia, and Germany. How these are used, who provides the necessary training, how interoperability/compatibility is ensured remain unknown.

- The Kuwaiti military still struggles with providing adequate training to the highly qualified personnel it requires to operate its recently purchased Patriot missiles.

Besides non-strategic defence purchases, an intermediary-rich supply chain in the procurement process is a too frequent caveat in the MENA region. Provisions and obligations for these agents rarely exist. A dedicated law was supposed to have been passed in Saudi Arabia, but no evidence exists supporting its enforcement. A similar situation exists in the UAE, where the government imposes legal restrictions on the use of agents and intermediaries in defence contracts; as no scrutiny exists, however, it is unclear whether these rules are respected. In Oman (ranking at the bottom of the index), all military procurement is exempted from public tender, and the majority of the contracts were found to be single sourced.

Defence and security personnel are frequently involved in private business in the MENA region in addition to their jobs in the military, but the profits they derive are rarely known. Egypt, Iran, and Yemen are among the most striking examples. In Iran, the Revolutionary Guards (also referred to as the Pasdaran) are estimated to have commercial interests worth “hundreds of billions of dollars”. Accurate figures are unknown. In Egypt, the army or ‘Military, Inc.’ as it is sometimes dubbed, is estimated to control a lion’s share of the country’s economy, a portion that exceeds the private sector share. In June 2015, the Egyptian Minister of Defence issued a special decree that exempts military facilities from real estate taxes, including on clubs and hotels. The profits received from these revenue streams have never been subject to oversight.

Openly available information identified further corrupt activities in the military in other MENA countries. In Yemen, for example, the armed forces were found to have participated in organised crime (fuel smuggling, human trafficking, among others), and a big chunk of the profits have been reverted to the military-run Yemen Economic Corporation. Yemeni and Tunisian military personnel have also been identified through OSINT to have been involved in illegal arms trafficking, reinforcing insecurity in the area. Moroccan legislation permits beneficial ownership of businesses by individuals in the military (e.g., fishing companies along the coast of the Western Sahara).

Collecting evidence about such malpractice and denouncing it matters, as corruption within the military is considered to be one of the factors driving support for ISIS. Credible reports suggest infiltration of oil smuggling networks overseen by Iraqi Army officers.

Other evidence supports Saudi Arabia’s involvement in arms passing to groups that are unable to purchase weapons themselves (due to sanctions or a lack of funds). Publicly available evidence highlighted that Saudi Arabia bought a large supply of weapons from Croatia on behalf of the anti-government rebels in Syria in 2013. Later, in 2014, the Kingdom funded the purchase of Russian arms, worth 2 billion USD, in the name of the Egyptian government.

—

Full reports on a per-country basis available at the dedicated website.

Transparency International’s Defence & Security programme also publishes a similar index focusing on companies.

An outstanding piece at Africa Confidential provides additional insights about Egypt’s “slush funds”.