Turkmenistan (#ItalianArms): A Dictator, Millions of Euros, and Italy’s Bureaucracy

Turkmenistan is among the world’s most repressive countries, and is largely closed off to the outside world. When it comes to press freedom, only North Korea and Eritrea are rated worse. The president and his associates have total control over all aspects of public life in Turkmenistan. Yet the country is nonetheless a major buyer of EU arms, with Italy supplying by far the biggest part.

We took a closer look at Italian arms deliveries to Turkmenistan — and traced a selection of arms despite the general lack transparency.

EU member states agreed in their common position on arms exports to reject licenses to countries that are known for domestic repressions. This agreement exists in addition to local Italian laws that state that “the export and transit of armament materials are also prohibited [to] countries whose governments are responsible for ascertained violations of international conventions on human rights.”

Both the agreement and the Italian law in question seem obviously applicable to Turkmenistan. Its government ruthlessly punishes any alternative political or religious expression and exerts total control over access to information. As Human Rights Watch states in their latest report: “Independent critics and their families, including [those] in exile, face constant threat of government reprisal… Dozens of people remain forcibly disappeared, presumably in Turkmen prisons.”

According to Reporters Without Borders and their 2018 World Press Freedom Index, Turkmenistan had the third worst press freedom conditions in the world (178th place out of 180 countries), just ahead of Eritrea and North Korea. And on The Corruption Perception index 2017 of Transparency International, Turkmenistan scores at 167 out of 180 countries — just after Angola and before Iraq.

President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov’s regime imposes human rights restrictions as an intentional, systemic policy meant to control every aspect of society. Berdymukhamedov has ruled Turkmenistan since December 2006 without gaining legitimacy via free and fair elections, much like his unelected predecessor.

Nonetheless, based on annual reports from the European Union, between 2007 and 2017 Turkmenistan bought arms for a total value of almost 340 million euros, 76% of which (a total of 257 million euros) came from Italy, making it Turkmenistan’s biggest supplier by far. Most countries report to the EU what their arms exports consist of, but, as you can see below, Italy does not. The complete export falls within the category of “miscellaneous.”

Source: ENAAT (Official Journal of the European Union annual reports on the European Union Code of Conduct on Arms Exports)

What armaments did Berdymukhamedov buy with his 257 million euros? Answering that question should have been easy, since a European agreement obliges EU member states to report on their exports on an annual basis. Italy does, but that doesn’t mean the information is easy to make sense of.

Illusory Italian Transparency

Data on licenses, export, and transit of arms is reported every year in a document addressed to the Italian Parliament by the Prime Minister. It is freely available and its aim is to create an overview of the Italian arms trade, as well as of the final destination of Italian-made armaments. It should give the members of parliament the tools to monitor their government on authorization granted for arm trades.

These Government documents (“GDs” for short) include reports made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Economy and Finance (specifically, its subset — the Department of Treasury and Customs Agency), the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Economic Development.

In these documents the relevant information, such as country of destination or product type, is separately presented in different tables of various documents. These tables have to be linked together to get a clear picture, but instructions on how to link them do not exist. As a result, the documents fail to provide a complete picture. This fragmentation of information is a major obstacle for effective monitoring of arms exports by parliament and civil society.

On top of that, the format of the documents — PDFs and PDF scans — does not allow for effective automated searches. The layout makes traditional OCR analysis techniques not applicable, because of the size and resolution of the tables and the risk of their misidentification during automated analysis. Additionally, the listed tables do not have a consistent order (with information sometimes written down from top to bottom instead of from left to right), information is often redundant, and the quality of the scans too low. The outline of the documents, as well as the tables, changes over the years, providing data in different ways and making it harder to apply the same methodology of data extraction in different years.

Decoding the GDs

We nonetheless were able to decode the information on Turkmenistan in some cases and must take a moment to explain our methodology.

A table by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, let’s call it the License Table, collects all the authorizations given by the Ministry for specific exports in a given year. However, it does not provide information on the destination country.

Information linked to destination countries has to be looked up in a table by the Ministry of Economy and Finance, let’s call it the Export Table. It presents the identification number (MAE number), the name of the company, the destination country and the breakdown of the amount paid during that year by the country to the company. Up until 2012, it also presented the total value of the authorization. Based on this total value of a license we can link the two tables and discover the country of destination for a certain product.

However, a license does not equal an actual export. Some licenses never materialize. So, how much exactly did Italy export to Turkmenistan?

For that information, one must find a table provided by the Customs Agency — the Transit Table — which belongs to the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

In most cases, licenses have been split up and delivered in different years. Therefore, the entire process has to be applied to the GDs for each different year.

Example: Tracing the Beretta ARX-160 Assault Rifle

One of the typical Italian arms being sold to Turkmenistan seems to be the Beretta ARX-160 assault rifle. The ARX-160 is a modular assault rifle developed for the Italian Armed Forces. It comes in different configurations, calibres, and upgrades.

These arms are regularly showcased during parades — like those held, for example, on the occasion of the Turkmen Independence Day. During the 2018 independence parade, held on September 27 of last year, the ARX-160 assault rifle and the GLX-160 grenade launcher are displayed by different units of the Armed Forces of Turkmenistan.

(The source for the above images is a state TV broadcast)

The parade was geolocated to Independence Square in Ashgabat (37°56’07.38”N, 58°22’43.81”E).

Tracing the ARX-160 in the GDs

The question is — can we check whether these rifles have been sold to Turkmenistan with the mandatory license?

In the Export Table we can find all the licenses granted to Beretta for Turkmenistan for which a payment was registered. Through their identification number we identified eight different export licenses, one of them is MAE 23219, authorized in 2011.

Source: Export Table 2011

In order to find out what types of products have been sold via this authorization, we have to check the License Table. This table is provided by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Since this table provides the company name but, for some reason, does not provide MAE number and the country of destination, the only way to link the authorization number to the list of exported products is to crosscheck the two tables and look for the exact same amount on the total value of the license in both tables.

Accordingly, we find that an amount of €3,870,156 linked to Fabbrica d’armi Beretta, can be found in both tables.

Source: License Table 2011

The search for the exact same total amount in the two tables is the only way we have to link an arms export license with a country of destination. At this point, we can confirm that Fabbrica d’armi Beretta obtained a license to sell ARX-160s to Turkmenistan — but we still don’t know if the transfer of goods actually happened.

To do so we need to check the Transit Table. This table is provided by the Custom Agency of the Ministry of Economy and Finance and lists all the transfers of military goods actually exported.

In order to find the information we are looking for, we need to search for the total amount authorized in the third column. Once more, we have to rely on the total amount authorized in order to link the information in the Transit Table to that of the License Table and the Export Table.

Finally, we can state that all the Beretta weapons listed in the authorization of MAE 23219 — including 3470 spare parts for the ARX160s — were shipped to Turkmenistan in 2011.

This only works with documents created up until 2013. From that year on, the Italian government decided to change the layout and content of the reports, and stopped, for some reason, communicating the crucial total value of a license in the Export Table.

Monitoring Italian Arms Post-2013

If you’re looking at data from after 2013, it becomes more difficult to monitor Italian arms exports.

Let’s have a look at the export license MAE 43444, which appears, for the first time, in the Export Table of 2015. We showed in the previous example that the first step to take in analyzing it is to look for the total value of the authorization in the License Table and the Export Table — and to see where they match.

In the GDs drafted since 2013, the total value of the authorization is not indicated in the Export Table. However, the table does display the breakdown of the payments made that year.

The payments list different categories. In order to know the total amount authorized, we have to sum up the values reported with “Importo Transazione” (Transaction Amount). How do we know? Not because it is in the manual added to the annual reports — that doesn’t exist. It is empirically derived. When the total amount is calculated including all categories, it cannot be matched with any amount in the License Table, making it impossible to find the authorization for which the payments were registered. But, when the total amount is calculated including only “Importo Transazione,” it is likely to match with one of the values in the License Table.

Nonetheless, when checking all the tables in the License Table document we still couldn’t find the value of €475,524 therefore understanding what specific goods were authorized under the license MAE 43444 for Turkmenistan in 2015 was impossible.

But the license number reappears in 2017 with a value of €52,836, exactly the amount needed to complete the total value of the license: €528,360. So, to detect for which authorization these payments were made, and therefore which license could be linked to this MAE, we had to look for the same exact value in the License Table of 2015. As shown in the following image, in this way we could find out that MAE 43444 referred to a license that authorized Beretta to sell to Turkmenistan 300 ARX-160 cal. 5.56x45mm rifles, as shown in the red box.

All of these 300 ARX160s were delivered in the same year, as shown by the Customs Agency in the Transit Table.

From the information released in the GDs for 2015, the year when the license was authorized and delivered, tracing what goods were delivered from Italy’s Beretta to Turkmenistan is impossible. Only based on the GDs released in 2017 — so, with a delay of two years — we were able to monitor what exactly has been granted and shipped to Turkmenistan.

Mission Impossible: License MAE 51614

Using the manual method presented here — let’s face it, it is pretty time-consuming — we can trace some of the arms exports, but not all. Let’s have a look at MAE 51614 license. This authorization is registered for the first time in the payment registry of the Ministry of Economy and Finance through Export table of 2015.

As explained for the previous example, we focused on values reported to be paid for “Importo Transizione.” This allows us to link the payments with their matching license.

We know the value of the partial payments of license MAE 51614 for each year, but the table does not provide the total value of a license. And since the partial payments cannot be found as such in the License Table, no authorization on the list can be linked to these payments.

The absence of information on authorization must be noted, because it is the only way we have to find out what arms are authorized to be sold. What we can do to understand which authorization may be MAE 51614, is to calculate the total sum of the amounts paid over the years — as we did in the previous example for MAE 43444.

The sum of all “Importo Transizione” values paid over the years for MAE 51614 is €4,374,254. Searching through the License Table for 2015, we discovered it does not match with the value of any authorization on the list.

We can find three licenses with a value higher than 4 million euros. If we now look into the registry of the Customs Agency, we can verify whether there is any record that matches these authorizations. The authorization for the value of €4,210,000 never appears in the registries of the Customs Agency — but the other two authorizations were fully exported in 2016, as you can see below.

However, when analyzing these payments in the Export Table for 2016, we can see that the authorizations for €4,000,000 and €6,000,000 were granted for deals with Iraq. Therefore, we can exclude that these two authorizations were granted to Turkmenistan and can be linked to MAE 51614.

The only authorization which is likely to be related to MAE 51614 is the one for the value of €4,210,000. Because of the lack of information on the total value of the authorization we cannot be sure that the identified license matches with MAE 51614. Therefore, we are not be sure about what kinds of arms were authorized to be sold, and when or if they were actually exported.

The only way it can be explained is if the total sum we calculated was just partial. There are two possible reasons for this. Either the payment has not been finalized yet — meaning that there will be GDs in following years without which the total sum is incomplete — or it was and will never be finalized, meaning that only a part of the products authorized were actually paid for and exported.

This lack of transparency is problematic, since the documents in question are supposed to allow the Italian Parliament to monitor Italian arms exports. The poor members of the Italian parliament are clearly being left in the dark.

An Open Source Approach to Monitoring Italian Arms

Monitoring Italian arms exports by relying on government documents is — in spite of European and domestic agreements — quite often literally impossible.

So, we decided to try something else and used open source data to get some sense of the situation with Italian arms on the ground in Turkmenistan. Below you’ll find a selection of Italian arms usa in Turkmenistan. We found these using open sources and tried to link them to the official paper trail.

The Beretta PX4 Storm

The PX4 Storm pistol is seen while being fired during a training held in the desert in the vicinity of Turkmenbashi on August 10 2018 — a session headed by president Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov himself (Source: Still taken from state tv broadcast footage; official government statement):

In 2011, the Italian Ministry of Foreign affairs allowed Beretta to sell 120 PX4 Storm 9x19mm pistols to Turkmenistan. It was part of the same license as the ARX-160 we discussed before (Authorization MAE 23219). Shipment and payments were confirmed in 2011 and 2012.

Missing Authorizations For Aircraft

At the 2018 parade for the Turkmen Independence Day, two AW-109s and two AW-139s of the State Border Service of the Armed Forces of Turkmenistan flew over Independence Square in Ashgabat:

The AW-139s in sand/green camouflage were spotted frequently, seen on the tarmac at Aktepe military airbase:

In 2011, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave AgustaWestland (a subsidiary of Finmeccanica, now known as Leonardo) the green light for the sale of five AgustaWestland AW-139 helicopters “for military use,” related piloting, maintenance training, and hardware support to Turkmenistan for €64,000,000 through authorization MAE 21998. Government documents confirmed the items on this licence were wholly exported by the year 2011 and payments made between 2011 and 2012.

However, the AW-139 wasn’t the only helicopter bought in Italy, as we also found a few AW-109s. Yet a thorough review of government documents between 2003 and 2016 has shown no authorization for, export to, or payment by Turkmenistan for the purchase of AgustaWestland AW-109 helicopters.

There is, meanwhile, abundant evidence of this aircraft being in the Turkmen Air Force fleet:

One possible reason these helicopters don’t appear in the GDs is because they can be fitted for civilian use. That, however, can be ruled out on the basis of visual analysis.

AW-109s with military camouflage have been spotted for the first time on Turkmenistan’s Independence Day in 2016. Non-official footage of the event shows three AW-109s flying over Independence Square in Ashgabat. One of them has the serial number 72.

Jane’s Information Group confirmed that three armed A109s flew over the capital during a military parade in Ashgabat in October of 2016 — as well as mentioned unconfirmed reports according to which these aircraft have been in the service of Turkmenistan’s military since at least 2012.

On November 16 of the same year, an AgustaWestland AW109E Power with distinctive Turkmen Air Force roundel was spotted at Varese-Venegono airport, where AgustaWestland and sister Leonardo subsidiary Alenia Aermacchi test their products, which are manufactured in adjacent facilities. This aircraft bore serial number 74 and was not equipped with rockets:

SIPRI’s Trade Registers note that the order for four AW-109s was placed in 2011, and delivered in 2016. One of the verified sources to SIPRI’s claims is a communique of contract for helicopter maintenance services that Italian company Alidaunia has reported on its website. The order specifies the goods the services were requested for, the “A109EP / AW139 fleet,” that is, and starting from when — in 2011. There is no specification, however, concerning the number of AW-109s in the aforementioned fleet.

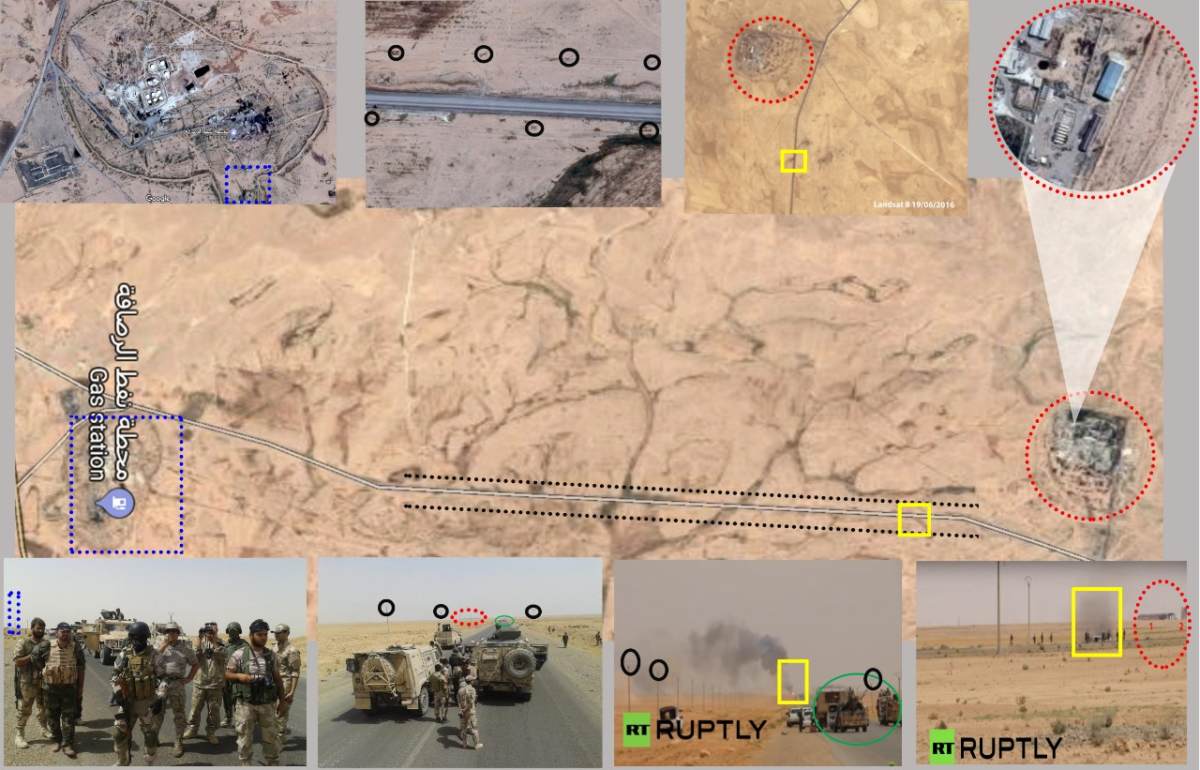

Rocket-armed AW-109 helicopters have participated in live fire drills during a wider training exercise close to the Turkmenistan border with Iran on August 1. 2017. Two AW-109s are seen launching rockets from side-mounted pods in this video edited by an opposition media group using state TV broadcast footage. The use of such aircraft during the event has been confirmed by Jane’s Information Group, but this time the location was identified. President Berdymukhamedov is filmed while presiding and watching the exercise from the border post facilities using binoculars, indicating that the live fire drills are occurring in the proximate vicinity.

The area where the AW-109s fire their rockets was geolocated (approximately at 37°48’47.42”N, 58°24’11.57”E) to the south of Ashgabat

Salvos of what appear to be unguided rockets seem to be launched by non-metallic 7-tube pods mounted on both sides of the AW-109s:

On one of the photographs attached to the official statement, two armed AW-109 helicopters — supposedly the ones which participated in the drill — are displayed on a helipad:

The site was geolocated (37°49’06.39’N, 58°23’36.53”E) to the southeast of Ashgabat:

During a January 17, 2018 visit, on which president Berdymukhamedov reviewed the helicopter fleet of the Armed Forces of Turkmenistan, among the aircraft on display there are at least three AW-109s sporting a typical brown/sand/green military camouflage pattern. One of them is serial number 70. This finding has presented us with the chance to carefully analyze the aircraft on the ground for the first time (Source; official government statement):

Geolocation indicates that the aircraft were stationed at Aktepe military airbase, northwest of Ashgabat (38°00’13.69”N, 58°12’01.90”E).

Two AW-109 helicopters can also be spotted on the tarmac at Aktepe military airbase on different dates via satellite imagery.

This AW-109 is photographed with FZ233 lightweight 7-tube composite pods for firing guided or unguided 70mm rockets mounted on its sides (same ones mounted during the August 2017 drill and probably the October 2016 parade as well):

These launchers are manufactured by Forges de Zeebrugge, a subsidiary of Thales Group, which holds a qualification to provide lightweight 70mm rocket launchers to the AgustaWestland EH-101 and the A-109, in its A-109LUH variant (the FZ233 is one of two available models for the 7-tube pod).

This variant has been rebranded AW-109M, a militarized version of the AW-109E. This is confirmed by Leonardo: The brochure for the AW-109M clearly states the possibility of installing 7- or 12-tube 70mm rocket launching pods, and a photograph of the 12-tubes FZ231 (same family as the FZ233) is shown among the possible configurations.

Additionally, the configuration of AW-109 helicopters in service with the Turkmen Air Force has been confirmed by Jane’s Information Group and by SIPRI’s Trade Registers, which list them as AW-109E Power. The Power is an improved variant whose military version has been acquired by many air forces, armies and security forces in the world.

As multiple sources, including the naked eye, have documented, the AW-109E Power in its military variant — the AW-109LUH or AW-109M — was in service with Turkmenistan’s Air Force since at least 2016, with at least three helicopters, whose serial numbers are 70, 72 and 74, respectively. This model’s armament’s capabilities have been amply demonstrated as well. At the same time, if one goes by government documents, it is not evident that a license was granted for the acquisition of these military helicopters by Turkmenistan between 2003 and 2016.

Missing Authorization: The AW-101

The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has authorized the sale of two AW-101s to Turkmenistan through licence MAE 22001 in 2011. The document approves the sale of AW-101 helicopters in “Utility” configuration (read Leonardo brochure for details on this configuration), including related spare and replacement parts. The total value of the license was for €103,410,594.

The AgustaWestland AW-101 is a medium-lift helicopter suitable for both military and civilian use. A press release published by Leonardo in April 2013 reveals that one AW-101 helicopter had been delivered to Turkmenistan Airlines, but this concerned a VVIP configuration, not the military “Utility” configuration.

Open source analysis reveals that currently at least two AW-101, both in VVIP configuration, are operated by Turkmenistan Airlines — their registration numbers are EZ5714 and EZ5715:

At the same time, at least two working AW-101 helicopters in VVIP configuration (recognizable by their white cabin and green tail) are regularly stationed on the tarmac at Aktepe military airbase:

We found no trace of AW-101s configured for military use in Turkmenistan. But, according to government documents, this deal was partially paid for. Between 2011 and 2012 €9,571,368.71 has been paid for spare parts.

It is possible that the two AW-101 helicopters in VVIP configuration were exported as civilian aircraft, hence free of any obligation to be registered as military goods. If that would be the case, authorization for military use was granted, but not used. And the spare parts — subject to arms export licenses as well — might have been used for VVIP-aircrafts. But, based on the GDs, we cannot tell.

The authorities dealing with licensing authorizations within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Customs Agency were contacted and asked to comment on the status of the AW-109s and the AW-101s bound for Turkmenistan. They recognized their jurisdiction on the matter but refused to divulge any information, despite the fact that authorizations we asked to clarify are supposed to be in the public domain.

Two (Or More?) Naval Cannons: The Oto Melara 40L70

The 40L70 is a naval cannon that is easy to install on various types of ships. It was jointly produced by the companies Breda and Oto Melara. Oto Melara was a subsidiary of Finmeccanica, today rebranded as Leonardo.

The mount can be used against a wide range of targets, including anti-ship missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles, conventional and rotary-wing aircraft, surface ships, small watercraft, coastal targets, and floating mines.

The Oto Melara mounts can be seen on a number of Turkmen Tuzla-class patrol boats. All of them are named “SG,” followed by a three-digit number. Examples are as follows:

SG 111 Arkadag:

SG 113 Merdana and SG 114 Erkana:

SG 115 Asuda:

SG 116:

SG 117 Husgar:

SG 118 Synmaz:

We have tracked the SG 113 and SG 114 docked at the navy base of Turkmenbashi (40°00’16.6″N 53°03’27.3″E). Both ships mount the 40L70, as shown in the images below:

In the same location, we were able to find additional SG patrol boats. The 40L70 units are, again, highlighted in red:

Additionally, a number of videos by Turkmen State television broadcaster, Watan Habarlary, show SG ships in action where the 40L70s are clearly visible.

Here are the links to the videos, followed by the times during which the ships and the cannon are visible:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLJNZfyIt70 22’30”, 22’33”, 22’58”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIgX4DWRTUE 11’10”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ICS4BYPhPLs&t=40s 25”, 2’41”, 2’47”, 3’27”, 3’53”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7CVxn2Zkwc 1’50”

The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs allowed Oto Melara to sell two 40L70 naval canons to Turkmenistan in 2011. The total value of the license (MAE 22559) was €6,990,000. Both the payment and the transfer were confirmed in 2011.

Based on the images presented above we can state that the number of Oto Melara 40L70s in use with the Turkmen naval forces exceeds the number we could trace in the official documentation publicized by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs since 2003. There are seven Oto Melara 40L70s being used by Turkmenistan. We could find documentation for just two.

The Exports Continue: The C-27J and M-346

On May 9, 2018, defense news media reported that the Turkmen Air Force was considering acquiring the Alenia C-27J Spartan tactical airlifter and the Alenia Aermacchi M-346 Master military advanced aircraft trainer from Leonardo. Reports suggested that on May 3, 2018, president Berdymukhamedov had reviewed the two aircraft and had been given a flight display at an airbase.

Footage acquired from state TV broadcasts revealed that president Berdymukhamedov did review the aircraft, including their cockpits and the C-27J Spartan’s cargo compartment, together with his air force officers (Source; official government statement):

Geolocation, initially focused on the surrounding mountain range, indicates that the aircraft showcase occurred at Aktepe military airbase (C-27J Spartan: 38°00’45.28”N, 58°11’26.20”E; M-346: 38°00’45.94”N, 58°11’25.81”E):

In particular, the two aircraft were lined up along the eastern runway on designated parking places. In the frame depicting president Berdymukhamedov driving the sand-coloured tactical vehicle toward the parking places, hardened aircraft shelters are visible in the right corner of the background, which in the satellite photograph are visible at the end of the lower runway. This indicates that the two planes are positioned northwest compared to the hardened shelters:

The C-27J Spartan is a multi-mission tactical airlifter and is described as capable to operate from short, rudimentary airstrips in extreme environmental conditions, while equipped with very advanced avionics. It’s overall a very robust and flexible platform ready to perform in a wide variety of roles, already tested by other major air forces.

The M-346 Master is a next generation advanced military jet trainer and is depicted as instrumental in developing piloting skills for the effective exploitation of modern combat aircraft. The M-346 can integrate different simulation devices to test a wide range of training capabilities for fighter pilots. The M-346FA version, an evolution of the basic trainer model, is itself a multi-role light fighter jet that still retains all advanced training capabilities.

As per the outcome of the evaluation phase undergone in Turkmenistan and the perspective of a sale of two of its leading products, Leonardo issued no press release, and did not provide comments on its website. Meanwhile the relationship between the Italian group and Turkmenistan seems well established by now, as the large procurements of a wide range armaments over the years show.

This possible sale may represent a further step ahead, a new dimension in which Italy and the Turkmenistan regime will cooperate: Fixed wing military aircraft. Following a potential purchase of the M-346 trainer in particular, the bond may be reinvigorated and open a new phase for the future acquisition of modern combat fighter jets, to replace Turkmenistan’s aging fleet of Soviet-era remnants.