The Arrest of Vladimir Tsemakh and Its Implications for the MH17 Investigation

Last week reports appeared online that the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) arrested Ukrainian citizen Vladimir Borysovich Tsemakh (b. 4 July 1961) in connection to the 2014 downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 (MH17). Tsemakh was previously known to have been the commander of an air defense unit in Snizhne, the town nearest to the Buk missile launch site. Tsemakh had not been publicly linked to the events surrounding the downing of MH17 before, and was also not mentioned in our recent report about the separatists connected to the downing of MH17. However, newly-surfaced footage has revealed that he was, at a minimum, an important eyewitness to these events.

Abduction and Arrest

Vladimir Tsemakh was reportedly abducted on 27 June 2019 in his hometown of Snizhne by Ukrainian agents, who knocked him unconscious and smuggled him out of separatist-held territory using fake documents and by disguising him as an old paralyzed man in a wheelchair. Novaya Gazeta reported that his arrest was easy because he was in alcohol-induced stupor at the time of the detention and abduction (his wife has also publicly stated that Tsemakh has an alcohol problem).

Two days later, a court in Kyiv gave way to a criminal case against Tsemakh, the charges document stating that he was suspected of committing a criminal offense under Part 1 of Article 258-3 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine — creating a terrorist group or a terrorist organization — a standard charge brought against separatists by the Ukrainian authorities. This was also confirmed by both his lawyer and daughter. However, because Tsemakh was reportedly, and self-admittedly, the head of an air defense unit in Snizhne in the summer of 2014, and considering the fact that Ukrainian special forces were willing to risk carrying out a dare devil raid behind enemy lines, the main reason for the arrest has been understandably and quickly linked by many observers to MH17.

Left: A photo of Tsemakh at Savur-Mohyla, south of Snizhne, dated 27 May 2018. Right: One of the post-arrest photos of Tsemakh that has appeared online.

On 2 July, Evgeny Tinyansky, an official of the self-proclaimed DNR (Donetsk People’s Republic), released more information about the arrest, including the first post-arrest photo of Tsemakh (sent to his wife by his Ukrainian lawyer) which showed he had a bandaged wound on his forehead. Tinyansky also provided a copy of Tsemakh’s military identification card from early 2015 which states that Tsemakh was the head of air defense within military unit 08801, also known as the 1st Slovyansk Brigade, with the rank of Podpolkovnik (Lieutenant Colonel) as of 23 October 2014. He added that prior to that date, Tsemakh was not in any air-defense unit but only a garrison commandant of a small military unit in Snizhne, thereby suggesting that Ukraine was mistaken in assuming that they could link him to MH17. Tsemakh’s daughter was also quoted as denying that her father had a commanding air-defense role prior to October 2014, alleging that he was a rank-and-file soldier manning a checkpoint at the time of the MH17 downing.

However, regardless of this particular document, there is ample open-source evidence that Tsemakh was in a commanding role of an air-defense unit at the time of the shoot-down of MH17, and certainly prior to 23 October 2014. For instance, Tsemakh’s Odnoklassniki profile reveals that he was serving in an air-defense unit at least as early as 24 August 2014, as he can be seen manning a vehicle-mounted ZU-23 anti-aircraft cannon on photos uploaded on that date. Furthermore, one of the photos shows the acronyms for the words “Anti-aircraft missile forces, Snizhne” written on the side of one of the vehicles:

A photo from he same album shows that “Anti-aircraft missile forces, Snizhne” was written on the side of one of the vehicles

In addition, on 5 July 2019, shortly after Tsemakh’s arrest, Igor Girkin (a.k.a. Igor Strelkov), the former Defense Minister of the DNR, refuted the DNR official’s defense argument. Responding to the arrest of Tsemakh on his VK profile, Girkin stated that “Borysych” (the reported call sign of Tsemakh, based on his patronym) was indeed the head of the air defense in Snizhne in July–August 2014, explaining that he had been appointed to this position by the military commandant of Snizhne — at the time this was either “Prapor” (Evgeny Skripnik) or his replacement “Kep” (Sergey Velikorodny). Girkin also added that prior to that, Tsemakh had served as a distinguished commander of mobile ZU-23 units in Semyonivka — a village near Kramatorsk which served as a base during the Battle of Slovyansk.

In his post, Strelkov once again denied that any of the separatists, including Tsemakh, had been involved in the downing of MH17, using carefully phrased statement which said that “Borysych” did not have under his control military equipment that could have shot down MH17. Girkin has previously repeatedly stated that separatists did not shoot down MH17, but has conspicuously refrained from blaming the Ukrainian side for the downing, leading to speculation that he is indirectly alluding to the responsibility of the Russian army.

Tsemakh’s later position as the air defense commander of the 1st Slovyansk Brigade also fits Girkin’s narrative, as this brigade consisted of units directly commanded by Strelkov since the Battle of Slovyansk. After the separatists withdrew from Slovyansk on 5 July 2014, these units were sent to Donetsk and the frontline settlements Mospyne, Ilovaysk, Shakhtarsk, Torez, and Snizhne. They were eventually reorganized into the First Slovyansk Brigade after Strelkov resigned as the DNR’s Minister of Defense on 14 August 2014.

On 5 July 2019, the Ukrainian news website The Babel reported that they had spoken to Ukrainian intelligence officials who stated that Tsemakh was allegedly involved in the transfer of military supplies from Russia and that he had been responsible for the air defense of his battalion. The Babel described Tsemakh as the head of an air defense battalion since 26 June 2014. They added that Ukrainian officials were now checking whether he was also involved in damaging Ukrainian military Su-25 aircraft in July 2014 (the Ukrainian Air Force lost several Su-25’s in the area south of Snizhne during this month).

Before the downing of MH17, the separatists were not known to be in possession of any high-altitude anti-aircraft weaponry. Girkin later wrote that his air defense weapons in the summer of 2014 only consisted of five 9K38 Igla MANPADS; about a dozen Zu-23 twin-barreled autocannons; a few more NSV machine guns; and a barely functional Strela-10 low-altitude anti-aircraft missile launcher. The latter was deployed south of Snizhe on 16 July 2014, as can be seen during a video interview with Girkin (in our recent report, we revealed that Oleg “Gyurza” Pulatov, one of the suspects linked to the downing of MH17, also appears in this footage).

Several old photographs in Tsemakh album on his service in the Soviet Armed Forces show ZSU-23-4 “Shilka” self-propelled anti-aircraft systems. The systems visible in the photographs likely are the ZSU-23-4M2 variant, which was adapted with night vision and without radar for the Soviet-Afghan war. Tsemakh is visible himself wearing a helmet standing in front of such a system in a few of the photographs, suggesting he was an operator or even commander of one of these air defense systems during the Soviet-Afghan war. One photograph from his service also shows a Strela-10, though there is no clear indication that he also operated this system.

An old photograph from Tsemakh’s service in the Soviet Armed Forces showing the ZSU-23-4 “Shilka” self-propelled anti-aircraft system

Newly-surfaced video footage

Additional open-source evidence of Tsemakh’s commanding role in the anti-aircraft defense separatist unit came from newly-discovered footage. On 6 July 2019, Twitter users discovered and posted links to a 2015 documentary (deleted on 9 or 10 July 2019, playlist archived here), containing a series of on-camera interviews with Tsemakh and other separatists. The 14-part documentary titled “Brother against Brother” was posted on YouTube on 19 June 2015 by a regional office of the Rodina party, a pro-Kremlin nationalist quasi-opposition party, which had produced the film as part of what it called a “humanitarian-cultural visit to the Donbas”.

In the sixth part (deleted on 9 or 10 July 2019, copy of the video here, archived link to the video here) of the series, recorded in early 2015, Tsemakh talks about supervising military operations south of Snizhne in the summer of 2014. During the interview, he is referred to as an anti-aircraft commander, which is also mentioned in hand-written notes from Tsemakh’s military diary that are shown during the documentary. The earliest entry shown is from 31 July 2014 where he already describes the use of ZU-23 anti-aircraft cannons:

An accidental video confession

More than simply evidence for his role in the air defense at Snizhne around the time of the downing of MH17, the footage with Tsemakh contains what appears to be a damning admission to his personal involvement in hiding the Buk missile launcher in the aftermath of its use on 17 July 2014. The third episode of the documentary (deleted on 9 or 10 July 2019, archived here on our YouTube channel) was mostly filmed near the village of Nikishino, where Tsemakh fought in the winter of 2015 during the Battle of Debaltseve. When traveling to Nikishino from the south, they stop at a crossing near Petropavlivka, a mining village just 1 kilometer to the north of the point where MH17 was hit by a Buk missile, and where part of the airplane debris had fallen. Tsemakh then talks about the downing of the civilian airliner:

Tsemakh: So, here’s where the Boeing fell, starting from Petropavlivka all the way to Hrabove… it was quite a big [debris] spread, like 10 kilometers… That’s the one, the Boeing that fell…

Short thereafter, а question by the interviewer is clearly edited out. From the context it appears that he asked if Tsemakh would prefer not to speak about the presence of a Buk missile launcher among the separatists that day. The conversation then proceeds with an apparent admission by Tsemakh that a Buk missile was fired from Russian and separatist-held territory and that he had a role in hiding the Buk missile launcher after the shoot-down of MH17:

Tsemakh: No, why not? I will tell you… It destroyed a Sushka [i.e. Sukhoi jet] — well, this, later, you know… [Tsemakh gestures to the camera as if he expects that this part will be cut out later] — it destroyed a Sushka, yes, and the other Sushka shot down the Boeing. I know about this. I pulled out that young guy, and I hid this *bleep* [Buk]. I will show you even where it lifted off, and where I picked it/him up [Tsemakh proceeds to laugh]

Interviewer: Thanks, Ilyich, thank you.

Tsemakh: No, seriously, you have no idea what was happening here.

Left: A still from the interview with Tsemakh’s apparent confession. Right: The location of the interview geolocated near Petropavlivka (coordinates 48.148829, 38.544846)

While the object that Tsemakh claims he was hiding is bleeped out by the film producers, his mouth movement clearly indicate that the word contains a “u” (“у” in Cyrillic) letter (in Russian pronounced “oo”).

Since the discovery of this video, some Russian bloggers and media have claimed that Tsemakh does not utter the word “Buk” in the bleeped-out segment, but instead the one-syllable word “khuy” (хуй), Russian for dick or dickhead. In this interpretation, he is alleged to be referring to the “dickhead” who he was “dragging out” [“прятал этот хуй”]. However, this explanation is inconsistent with the timing of the speech segment, with Russian grammar, and with the context of Tsemakh’s narrative. If Tsemakh indeed had uttered “I hid this dickhead”, in Russian he would have had to use the accusative case for animate objects [“прятал этого хуя”], which would have required 5 syllables to fit within the bleeped-out section of his interview (“..э-то-го ху-я…”). If he had uttered “I hid the Buk”, only 3 syllables (“…э-тот Бук”) would have to fit under the bleep. If Tsemakh were to say the three-syllable utterance of this phrase, it would be “прятал этот хуй” — “I hid this dick” (object), rather than the five-syllable “I hid this dickhead” (person), which while technically possible is obviously illogical for the circumstances described in the interview.

An experiment using Yandex’s advanced text-to-speech (TTS) engine shows that only thе second hypothesis (“этот Бук”) is possible, as the 5-syllable utterance would not fit under the beep. To conduct the experiment we applied Tsemakh’s speech cadence to Yandex’s TTS voice engine (by selecting simulated voice “Ermilov”). We ran two scenarios: in the first one, we synchronized a computer-generated phrase saying “I hid that dickhead” (“Я прятал этого хуя”) to overlap with the start of the un-bleeped sound “I” (“Я”) in the original recording. In the second scenario we superimposed the phrase “I hid that Buk”, again synchronizing the beginning of the phrase with the unredacted audio.

As can be seen from the graph below, only in the “Buk” scenario there was no tangible desynchronization between the original and the simulated speech.

The two resulting audio files can be heard here: scenario “Khuy” and scenario “Buk”

In addition, the context of the statement would make little sense if he had spoken about “hiding a dickhead”, as this reference would be disconnected to both the preceding sentence (“it hit a Sushka”), and to the subsequent one (“I will show where it/he lifted off”). All of the scenarios around the “dick” or “dickhead” scenario make little sense when considering grammatical and phonetic circumstances; however, this segment of the interview makes perfect sense when assuming that he said “I hid the Buk”.

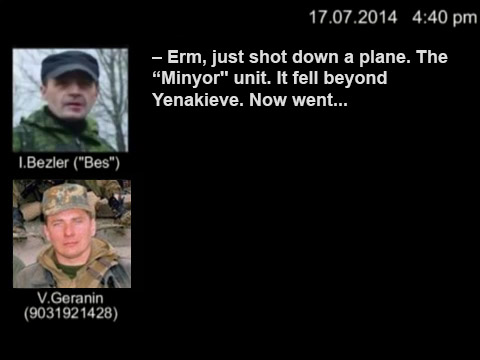

Despite his position as an air-defense commander, Tsemakh was most likely not involved in the actual downing of MH17. There is no indication that he has ever been trained to operate a Buk anti-aircraft system, and the recorded telephone intercepts have indicated that the Buk crew came from Russia. In our recent report we have also demonstrated that it was officers of the GRU DNR that were involved in the procurement of the missile launcher on the side of the separatists, though nothing indicates that Tsemakh was a member of this unit himself.

Nevertheless, the line “I pulled out that young guy, and I hid this [Buk]. I will show you even where it lifted off, and where I picked it/him up” in Tsemakh’s confession suggests that he was involved in hiding the Buk missile launcher and at least one of its crew members after the downing. There are hardly any details about the movement of the Buk during the aftermath. According to a reconstruction by the official Dutch-led Joint Investigation Team (JIT), the Buk was driven back to Snizhne autonomously after the downing, though they did not clearly specify at what time. One recorded phone intercept from 9:32pm between GRU DNR members Leonid “Krot” Kharchenko and Eduard “Ryazan” Gilazov reveals that the removal of the Buk and its crew did not go according to plan, as one of the Buk operators lost his colleagues and had to be escorted to Snizhne from an unspecified checkpoint. Some have suggested that this was the “young guy” that Tsemakh referred to in his confession, but it is unknown if this is true.

Not everything that Tsemakh stated in his confession is true, as he also mentions a conspiracy theory that the Buk shot down a Ukrainian Sukhoi military plane, while at the same time another Ukrainian Sukhoi shot down MH17. This theory is not new, as it was also discussed by members of the Oplot Battalion who filmed their arrival at the crash site near Hrabove shortly after the downing of MH17. A full transcript of this footage reveals that even after the men realized that a civilian aircraft had crashed, they were still convinced that their side had also downed a Ukrainian Sukhoi jet, and as such continued a search for pilots. One commander can be heard saying: “they say the Sukhoi [fighter jet] downed the civilian aircraft and ours brought down the fighter [jet]”. Later, another militant at the crash site says: “the fighter jet brought down this one, and our people brought down the fighter [jet]. They decided to do it this way, to look like we have brought down the [civilian] aircraft”. This narrative, however, is not supported by any evidence (no evidence of a Ukrainian airplane downed on 17 July has been presented by either side of the conflict; it is directly contradicted by Russia’s own radar data from 2016), and also contradicts the findings of the DSB, JIT, and Russian state-owned Almaz Antey, who all agree that the weapon that shot down the Malaysian airliner was a Buk missile and not an air-to-air missile.

Covering tracks

Why only the word “Buk” has been bleeped out in the documentary is unknown. Perhaps the editor was asked to remove the part of the interview in which the Buk was mentioned, and chose to leave the rest of the conversation in without realising that it could still implicate the separatists. Anyway, now that the fragment has been discovered and Tsemakh arrested, the people involved in the documentary seem unhappy about it.

At one point, the regional office of the Rodina party has disabled the website where it hosted links to the documentary. The videographer who shot the documentary, Alexander Vinchenko, has recently deleted an upload of this segment of the documentary from his own YouTube account, while he still keeps online the documentary parts that do not contain interviews with Tsemakh. We approached Vinchenko via his VK account to ask why he had deleted the video, and what word(s) were bleeped out and why, but he did not respond to our questions by presstime. Novaya Gazeta reported that it approached the interviewer Vyacheslav Kotsenko (a Cossack and regional leader of the Rodina party) with a question if he remembers what the redacted segment of the interview contains. Upon hearing the question, Mr. Kotsenko disabled public access to his social media account. (Update: as of 9 or 10 July 2019, the documentary has also been deleted from YouTube).

Relevance of the arrest for MH17 case

Whatever his actual role on 17 July 2014, Tsemakh’s arrest may have a significant impact on the JIT investigation and the pending court procedure. If his 2015 claims that he helped to hide the Buk missile launcher and part of its crew on 17 July 2014 turn out to be true, this would make him a key witness to JIT, and possibly an indicted suspect on counts of complicity and obstruction. Even if he was exaggerating his role on the day of the downing, in his position as local anti-aircraft unit commander he would have been well informed to make him a valuable witness to the prosecution.

The fact that he is currently charged in Ukraine on grounds unrelated to MH17 may be an indication of a strategy of the Ukrainian authorities and possibly JIT to offer him a deal with the prosecution and drop Ukraine’s criminal charges if he becomes a voluntary witness in the JIT case. Such a solution would ensure his physical presence in court in the Netherlands, which could not be ensured if he is indicted in the MH17 case due to constitutional constraints (a provision in Ukraine’s constitution prohibits extraditing its citizens to foreign nations).

Tsemakh’s testimony in court would strengthen the legitimacy of the court proceedings, as it is so far not known that another person of interest with direct involvement in DNR’s military operations at the time and place of the downing has been detained. A person with his prior role will be able to shed light not only on the specific event on the day of the downing, but also on the chain of command, which will be a crucial line of inquire for the Dutch courts.

At the same time, the value of his possible testimony will be attacked by the Russian side, especially given the circumstances of his arrest. Russian and DNR commentators are already spreading a narrative that Tsemakh may be “drugged” into induced confessions. The crucial question that will decide his relevance to court is therefore if he will be able to support his testimony with objective evidence. While he may be away from home without physical access to his archives of documents, he is likely still in possession of his online credentials.