Yes, It’s (Still) OK To Call Ukraine’s C14 “Neo-Nazi”

This week, a Ukrainian court ruled it’s not OK to call a neo-Nazi group a neo-Nazi group.

In May 2018, a tweet from Ukrainian independent media outlet Hromadske, on its international English-language Twitter account, described C14 as “neo-Nazi.”

“Neo-nazi group C14 has seized a former militant of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”, Brazilian Rafael Lusvarghi, and were going to hand him over to #Ukraine’s Security Service, one of the group members posted on Facebook,” the tweet read, referencing C14’s extralegal seizure of a Brazilian man who had allegedly fought with Russian-led forces in eastern Ukraine.

In response to this tweet, C14 sued Hromadske. On August 6, 2019, a court in Kyiv ruled in C14’s favour.

As Hromadske’s own story on the verdict reports: “[the] court noted that the information circulated by Hromadske back in May 2018 “harms the reputation” of C14 and ordered Hromadske to refute the information and pay 3,500UAH ($136) in court fees to C14.”

But, as we explain here in this brief investigation, the phrase “neo-Nazi” should be used to describe C14. The group’s past and present use of common neo-Nazi symbols and its violent rhetoric and actions make one thing clear: it’s completely justifiable, despite what a Ukrainian court has just ruled and despite their efforts to sanitize their public image, to call C14 “neo-Nazi.”

Who calls neo-Nazis by their name?

The ruling shocked human rights groups, journalists and other observers both inside and outside of Ukraine. Even the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media tweeted its concern about the ruling, arguing that it “goes against #mediafreedom and could discourage journalistic work” in Ukraine.

Despite losing the court case, Hromadske has pledged to appeal, and doesn’t appear to be backing down. One of their first responses was to call C14 “neo-Nazis” once again. “The Neo-Nazis Who Don’t Want to Be Called Neo-Nazis,” blares the title of an article published on their website on August 6, hours after the court ruling.

But it’s not just Hromadske who have used the word “neo-Nazi” to describe C14. International outlets from Israel’s Haaretz, Reuters, Washington Post and, of course, Bellingcat have used the term “neo-Nazi” in reference to C14. Unlike Hromadske, none of these outlets have been sued.

Additionally, “government bodies, such as the British Parliament, have referred to C14 in a similar manner. Human rights organizations, such as the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, have also referred to C14 as “neo-Nazi,”” Hromadske writes.

The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, in an article published the day after the ruling, points out that C14 is “considered by most experts to be neo-Nazi.” The Group points out that a number of experts and observers of the far-right in Ukraine frequently have referred to C14 as “neo-Nazi.” These experts and observers include Vyacheslav Likhachev, the author of a 2018 Freedom House report on the far-right in Ukraine, as well as academics Anton Shekhovtsov and Andreas Umland.

C14 has also had a former member describe them as neo-Nazi. “C14 are all neo-Nazis,” Dmytro Riznychenko told Radio Svoboda in 2018. “It’s quite an appropriate definition.”

Just months before, Riznychenko was beaten in his Kyiv office. He claimed C14 was responsible — he had a public falling-out with the group and head Yevhen Karas — but Karas denied C14 was responsible; Riznychenko also said at the time he declined to give a statement to police about the alleged assault.

Why the number 14 matters

The ‘14’ in C14’s name is more than just a number.

For its part, C14 claims that ‘C14’ is meant to resemble the Ukrainian word ‘СІЧ’ (“Sich”), and that the ‘14’ in their name refers to the mythical founding date of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) on October 14, 1943. But these explanations have never convinced watchers of the far right.

The ‘14 words’ are a well-known white supremacist, neo-Nazi slogan, as Matthew Feldman, Director of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR), explained to Bellingcat. “While it’s possible, given the 14 words’ formulation, to be ‘only’ a white supremacist slogan,” Feldman told Bellingcat by email, “I feel its neo-Nazi context is pretty well appreciated by friends and enemies alike.”

“Put simply,” Feldman added, “it’s a neo-Nazi phrase and anyone using it for different purposes….is doing it wrong, either through naivety or deception.”

C14 can’t claim ignorance; they’ve used the actual ‘14 words’ themselves. On a social media post for a “Youth Football Cup” the group hosted in 2011 — one, as we explain later in this article, they claimed was “for white children only — C14 includes the 14-word slogan, in English, at the bottom of the post.

“Youth Football Cup: For White Children Only,” reads a post from a social media page for C14’s “Youth Football Cup” in 2011. The ‘14 words,’ in English, are written underneath the post.” (Social media/Hromadske)

Feldman also argues that the “C” in C14’s name is “clearly modelled on the neo-Nazi ‘Combat-18’ group that appeared in the UK in 1992.” Feldman is not alone in arguing this; as Vyacheslav Likhachev argued to Hromadske, “[the] Latin letter “C” (stands for “combat”) – in conjunction with numerical neo-Nazi symbols – is also found in other neo-Nazi organizations.”

“The allusion to the 14-word slogan in the organization’s name, as well as the systematic use of other signs,” Likhachev told Hromadske, “…give full justification for claiming that C14 systematically uses neo-Nazi symbolism and is neo-Nazi.”

Celtic crosses, runes and black suns

There are two well-known neo-Nazi symbols that C14 has made regular use of in the past. The Celtic cross, as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) points out in its Hate Symbols Database, is a common white supremacist, neo-Nazi symbol, particularly when it’s used in a short “sun cross” version, exactly as C14 has used it in the past. It’s also, ADL points out, the logo of Stormfront, one of the internet’s first and largest neo-Nazi hate sites.

The Celtic cross that C14 has used in the past, as seen from their own social media posts, is identical to that commonly used by other neo-Nazi groups.

C14 members carrying a flag emblazoned with a Celtic cross, a common white supremacist, neo-Nazi symbol.

A photo from C14 social media of C14 graffiti featuring a Celtic cross, a common white supremacist, neo-Nazi symbol.

C14 members carrying a flag emblazoned with a Celtic cross, a common white supremacist, neo-Nazi symbol.

Yevhen Karas and C14 members hoisting a flag with a Celtic cross at the Kyiv city hall during the 2013-14 revolution.

The symbol has been so commonly used it sometimes appears multiple times in the same photo.

A photo from C14 social media showing graffiti originally reading “class war” altered to read “race war” — another neo-Nazi concept — with Celtic crosses.

Even the co-founder of C14-linked Education Assembly, Mykola Panchenko, got into the act.

In the town of Malyn, C14 “rebranded” a local far-right group into what they called “C14 Malyn.” The group’s name before C14 rebranded them was “White Pride Malyn,” and its logo was a Celtic cross. C14 itself shared news of the group’s rebranding.

The other neo-Nazi symbol C14 has made regular use of is a Tyr rune. Part of the Nazi regime’s appropriation of ancient European imagery, the Tyr rune resembles an arrow pointing upwards, and was used on badges of the Sturmabteilung (Stormtroopers) training school in Nazi Germany as well as by a Waffen SS division.

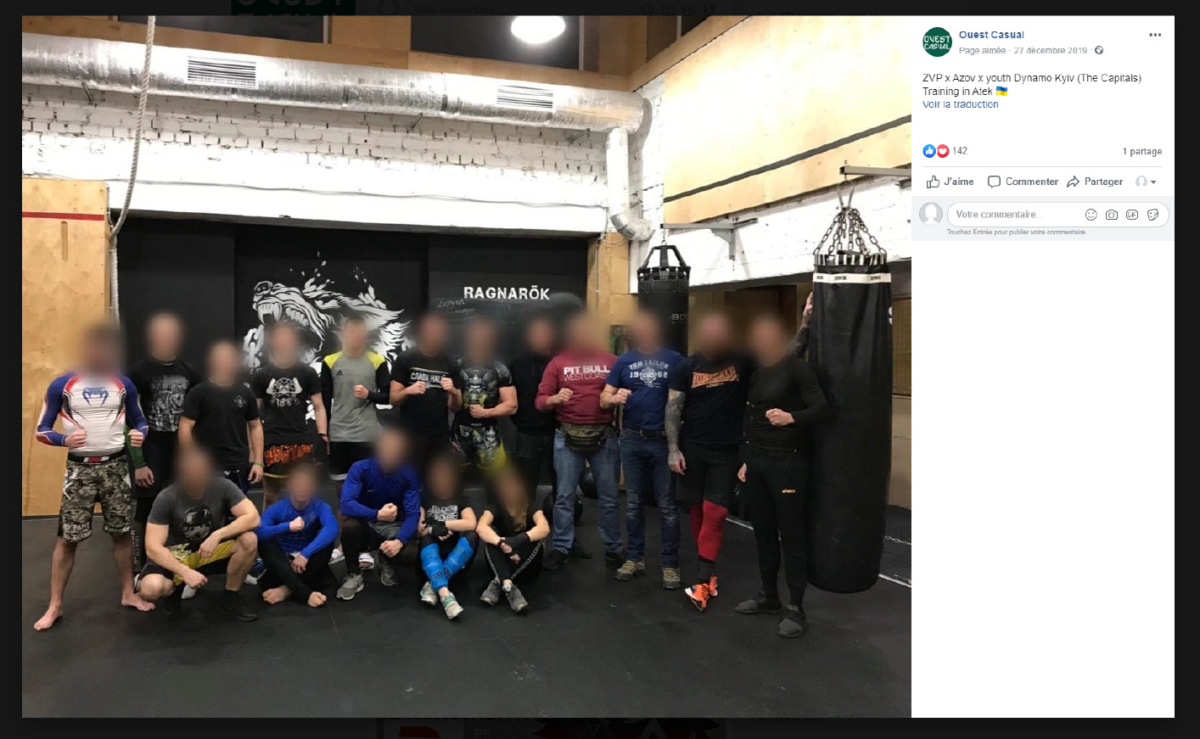

It’s not just C14 who has made use of the Tyr rune; for example, the logo of the Azov movement’s “leadership school” — which, as we pointed out in a previous investigation, receives Ukrainian government funds for some projects — resembles a Tyr rune.

A video from a C14 march in 2013 shows the group using both of these neo-Nazi images.

“Sport, Health, Nationalism,” reads a C14 banner featuring a flag with a Celtic cross as well as a Tyr rune, both common white supremacist, neo-Nazi symbols.

Also, as we pointed out in our previous investigation, Education Assembly’s logo, on its outer edges, resemble a sonnenrad, a well-known neo-Nazi symbol that was used by the Christchurch shooter.

The same sonnenrad is also visible on tattoos of C14 members (and, for that matter, members of other far-right groups in Ukraine).

A photo from a June 2019 protest march in central Kyiv organized by C14 to raise awareness of Ukrainians held captive in Russia. The young man on the right has a sonnenrad tattoo, as well as visible sig runes – the symbol of the SS – in the middle of the tattoo.

When neo-Nazis do neo-Nazi things

Organizing a football tournament “for white children only” sounds like the sort of thing a neo-Nazi group might do. It’s something C14 did in 2011.

As shown above, C14’s “Youth Football Cup” was promoted and branded with overt neo-Nazi imagery, from Celtic crosses to the 14 words to the printed slogan “for white children only” clearly visible.

A banner for C14’s “Youth Football Cup” in 2011, with a member giving a Hitler salute on a banner bearing a Celtic cross, a well-known neo-Nazi symbol. (Social media/Hromadske)

Since that time, C14 may have tried to clean up its image and push back at being called neo-Nazis; for example, the organization makes little if any use of the Celtic cross anymore.

Some C14 activists don’t seem to have got the message. Bellingcat found one self-described C14 activist who, before her public Instagram account was apparently banned earlier in 2019, posted pictures of herself with a Nazi flag and a shirt bearing the words “Meine Ehre heißt Treue” — “my honour is loyalty,” the motto of the SS.

Photos from a since-removed Instagram account of a self-described C14 activist, including a Nazi slogan and a Nazi flag.

Another individual’s public Instagram posts show them at a C14 march while wearing a C14 bandana over his face, while wearing a t-shirt of Kyiv-based, Russian-Ukrainian neo-Nazi movement Wotanjugend.

Photo of a young man participating in a C14 march and wearing a C14 bandana as well as a t-shirt of neo-Nazi movement Wotanjugend.

Wotanjugend, affiliated with the Azov movement, is an openly neo-Nazi movement that praises extremists like the Christchurch shooter, whose manifesto the group translated into Russian on their website. Wotanjugend even hosted an event in May 2019 called “Fuhrernight” which featured Nazi flags and photos of Adolf Hitler on an altar surrounded by candles.

Photo of a young man participating in a C14 march and wearing a C14 bandana as well as a t-shirt of neo-Nazi movement Wotanjugend.

C14’s founder Yevhen Karas is himself no stranger to giving Hitler salutes.

An undated photo of C14 founder Yevhen Karas, middle, giving a Hitler salute. (Social media/Hromadske)

But C14 has done more than just talk or use symbols and gestures common among neo-Nazis. The group has a long history of violent actions against minorities, including Roma, and individuals it arbitrarily accuses of being “separatists.” It has even earned the distinction of having two of its leading members on trial for murder (though the two men deny the charges).

“Enough ‘sieging,” [i.e., giving Hitler “Sieg Heil” salutes] it’s time to act!” reads a post on C14 social media promoting violence.

In addition, C14 openly act as vigilantes, as we observed in our previous investigation about the C14-linked street vigilante group, “Knights of the City” (Лицарі Міста), who have allegedly assaulted individuals it believes are intoxicated in public; C14 has also openly offered up their violent services as “thugs for money.”

C14 on the defensive?

But even with an apparent victory on August 6, C14 seems to be a group on the defensive. According to Ukrainian journalist Samuil Proskuriakov, C14 “numbers 150-200 activists across Ukraine, of which 60 to 70 are based in Kyiv,” while Ukrainian think-tank Institute Respublica, in a recent analysis, estimates that C14 has approximately 350 activists. Regardless of the differences in the range of estimates, there’s no doubt C14 is considerably smaller than the largest and most dominant Ukrainian far-right movement, the Azov movement, which claims to have approximately 10,000 “active members.”

During Ukraine’s presidential elections earlier this year, C14 was largely seen as pro-Poroshenko movement, or at least a movement opposed to Poroshenko’s two main opponents, Yulia Tymoshenko (who at one time was seen to be Poroshenko’s primary challenger for the presidency) and now-president Volodymyr Zelensky. C14 stood alongside other smaller far-right groups during the campaign like Tradition and Order (Традиція і Порядок) and Unknown Patriot (Невідомий Патріот) in this regard.

On the other side, the much larger Azov movement was openly (and violently) anti-Poroshenko throughout the campaign, taking the side of the figure largely perceived to be their patron, interior minister Arsen Avakov. Conversely, C14 has long been assumed to be linked to Ukraine’s security services (SBU).

It’s entirely possible that this year’s election results have C14 worried, both the presidential elections which saw Poroshenko trounced and the parliamentary elections which saw Poroshenko’s party finish fourth with only 8 percent of the vote. Worse for C14 is that the patron of their (sometimes) rivals in Azov, Arsen Avakov, looks set to keep his position as interior minister, which could well help Azov solidify its place as the dominant force on Ukraine’s far-right scene.

And it seems C14 is worried. After our Bellingcat Monitoring Project tweeted in early June that a C14 leader, Serhiy Mazur, followed an anti-LGBT account on Telegram, C14 responded with a 500-word response on its own channel, claiming that they “haven’t hit or attacked anyone” at KyivPride over the last five years (though C14 was part of a group in 2018 that tried to block the KyivPride march route, some of whom allegedly attacked police with gas canisters). This was all because we mentioned a senior member in passing in one Twitter thread.

It’s also worth noting that Bellingcat, at the time of publication, could not find a single mention of C14’s apparent victory in court on any social media account run by other Ukrainian far-right groups. C14, for all the celebrating it’s doing this week, is apparently doing so alone.